- Home

- Allan Jenkins

Plot 29

Plot 29 Read online

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2017

Copyright © Allan Jenkins 2017

Except Foreword copyright © Nigel Slater 2017

Allan Jenkins asserts the right to be identified as the author of this work

This book is based on the author’s experiences. Some names, identifying characteristics, dialogue and details have been changed, reconstructed or fictionalised.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008121969

Ebook Edition © March 2017 ISBN: 9780008121983

Version: 2017-02-15

Dedication

For Christopher

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

Nature

Cast list

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

December

Postscript

Acknowledgements

Photographs

Permissions

About the Publisher

Foreword

There are two sorts of gardeners, those who inherit a plot of land and cover it with a lawn, a neatly manicured patch of grass to trim and mow in straight lines for all to admire. Others use their space to grow, nurture and share. They dig deep, they replenish the soil, plant seed and watch it grow. They protect and nurture what lives there, and then they share the bounty.

You can go about writing a memoir in two ways too. You can pen a story that plasters over the cracks, telling tales of heroism and success. Or you can break ground, dig deeper, bravely unearthing an altogether richer story. One that takes its author and its readers down a track that is by turns surprising, tender and, occasionally, unsettling.

I have never read anything quite like Plot 29. Yes, it’s the gentle, heart-warming tale of the rescue and repair of an abandoned allotment, of protection offered to the soil by someone who understands the joys and pitfalls of growing. But contained in these pages is also an extraordinary memoir, brave, exquisitely written and utterly compelling.

Nigel Slater, 2017

Nature

When I am disturbed, even angry, gardening is a therapy. When I don’t want to talk, I turn to Plot 29 or to a wilder piece of land by a northern sea. There among seeds and trees my breathing slows, my heart rate too. My anxieties slip away.

It’s not always like that. Sometimes I just want to grow potatoes surrounded by flowers, like I did aged five with my brother one magical summer with our new mum and dad.

Plot 29 is on a London allotment site where people come together to grow. It’s just that sometimes what I am growing along with marigolds and sorrel is solace. I nurture small plants from seed like when I was small and needed someone to care for me. I offer protection from predators like when I tried to guard Christopher.

This then is my journal and childhood memoir, though my memories are fractured like my family. So I immerse myself in the plot, in nature and nurture. I lose myself in rapture. I grow fresh peas for my peace of mind.

It’s not all about healing, of course, though it’s there in abundance like beans. Sometimes it is the simple joy of growing food and flowers and sharing with people you love.

Cast list

Allotment family

Mary, Howard, Annie, Bill, Jeffrey, John, Ruth

Family

Henriette: wife

Christopher, Lesley, Caron, Susan, Michael, Mandy, Adeboye, Tina: brothers and sisters

Lilian and Dudley: mum and dad

Sheila: mother

Ray: father

Billy and Doris: grandparents

Terry, Tony, Colin, Mike, Joyce: uncles and aunt

Allan, Alan, Peter: me

June

By God, the old man could handle a spade.

Just like his old man.

Seamus Heaney, Digging

It is the month of early visits, of waking before 5am when the plot calls. The time of growth and hazel wigwams. Time to be concerned about seed. I lie awake – or sit at work – imagining the tender seedlings at the mercy of wind, rain, sun, slugs. Will they make it through infancy? With my help, maybe.

By 6am I am at the allotment, the air soft, the light too, the robin, maybe the fox, my only companions. The baby beans, only two leaves tall, are vulnerable now. Will they make it past the snails lying in wait like bullies? Within two weeks they will be free, snaking up hazel poles in a speeded-up film. Next month they’ll be two metres high, stems entwined, feeling for the next stick like rock climbers on a difficult face. Flowers will start to grow, pods begin to form. But for now I stand on the sidelines, a parent on sports day, calling urgent encouragement. Soon, like kids, they will be old enough to fend for themselves but for now at least I am here, not so much to do anything – the bed is hoed, weeded, pretty pristine – but as a friend, odd as this sounds, so they know they are not alone.

I learned, I think, to love from seed, much as other kids had puppies, kittens, fluffy toys. But it was the hopeful helplessness of seed that called, something vulnerable to care for. The urge to protect, to be there, was strong, like I couldn’t be for my brother Christopher when I left him alone in the children’s home; for my sister Lesley, out of harm’s way, I thought, with her dad, or Caron, whom my mother would abandon while she searched for new men, new sex, excitement.

SATURDAY 6AM. Sunlight has not yet hit the plot. Bill is sleeping less well since his wife died, so he comes here to kill time until Costa Coffee opens at 8am and he meets with his fellow insomniacs. His is the tidiest plot, manicured almost, everything neat in formal rows, plants perfectly spaced, celery blanching in brown paper, runner beans climbing up curly wire, blackcurrant bushes shrouded by nets. His seedlings are grown at home and transplanted into regimented rills. It wouldn’t work for me. I obsessively grow from seed in situ, needing the magical moment when an anxious scan along a row is rewarded by broken soil, a tiny stem breaking through like a baby turtle released from the egg before its dash to the sea. It has been two weeks since I have been here, and the salads have overgrown. Rows of rocket flowers shaped like ships’ propellers, land cress crowned with yellow spikes. The beans are under siege from slugs. Many inch-high stems are decimated, stunted, the baby-turtle equivalent of gulls swooping yards from the shore. Some have been simply obliterated. There is a sappy, fast growth to much of the plant life, perfect for predatory snails. Something has stripped a broad bean pod, though there are still many left. I walk through dew-soaked leaves and throw a few slugs over the wall. I will return later to pull much of the salad and let light in on the denser growth but the afternoon plan is to clear more of Mary’s beds.

>

Plot 29 belongs to Mary Wood, who has shared it with my friend Howard Sooley and me since 2009, when Don, her husband, died. Not because she couldn’t cope with the space (she is a gifted gardener) but because it produces more food, she says, than she can eat. Mary is poorly at the moment. As her energy levels have dropped, the weeds, the wild, have pressed in, strangling the plot. I am here to clear her green manure. Narcotised bees are everywhere, seemingly overdosing on nectar. They fall stoned to the soil as I clear. Sycamore seedlings infest the bed, the overwintered chard is blown, a metre tall, menacing nettles taller. I work quickly, scything, clearing, restoring order. It feels important now that Mary’s plot doesn’t also succumb to attack.

I clear the bed, transplanting a couple of short rows of six-inch chards, sowing another of beetroot seed. I return later to talk to her. She is here less than in previous years but sunshine and a need to replant sweet peas has drawn her out. She has a chair on the allotment now, and sits more often. We talk about what she wants to grow this year, and where. I cut pea sticks for a row at the bottom of the bed. With little time to work our part of the plot, I sow nasturtium on the border.

My gardening life, in some ways my life, begins with this simple seed. Most of my memories start at the age of five, perhaps because there are photos from then, perhaps because almost everything before then was chaos to be peeled away later in the therapist’s chair and in talks with members of my ‘birth family’ (a sly phrase we have been taught to say instead of ‘real’), when I found them many years later. Perhaps simply because that is where safety starts. With Lilian and Dudley Drabble.

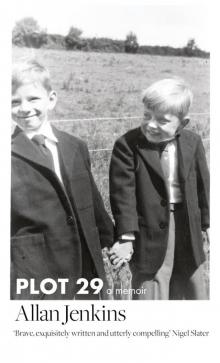

There is a photo of my brother Christopher and me with Lilian as young boys. Christopher is lopsidedly smiling, proudly holding his new ginger kitten. It almost matches his hair. Lilian is crouched with Tonka, her Siamese cat. I have my arm around her, looking a little warily into the camera. The boys’ clothes are comically big. Not ‘you will grow into them’ big, but clothes bought while the intended children aren’t (have never been) there. We were small for our age. But these are new clothes for a new life in our new home with our new family.

Lilian and Dudley married in their forties. They met when she nursed his dying father. Too old to have children, they at first looked to adopt a baby girl but were denied, perhaps because of age. It was a loss Lilian would always feel. She wanted someone all her own, someone she could mould and make, who would wear dresses. There was somehow always a sadness we couldn’t assuage.

Meanwhile, the Drabbles offered respite to ‘damaged’ children at their picture-postcard post office on Dartmoor. Christopher and I spent a weekend there, shooting bows and arrows, learning to say please and thank you (we were ‘guttural’ Dudley would later delight in telling me).

Plymouth children’s homes were feral then. Snarling packs sniffing out fears, tears, blood. Not always only the boys.

We learned a lesson about caste here. First, of course, there were the Brahmins: the ‘Famous Five’ families with their normal ‘mum and dad’ (small words still able, occasionally, to conjure black holes of unhappiness).

The adopted were the ‘chosen ones’, mostly children of the over-fertile underclass taken in by the infertile middle class. The unworthy become worthy, if you will; a shift in status almost impossible to imagine – a parole from purgatory.

Foster families were holding pens – a sifting, shifting, near-family life spent waiting. Here we would practise being appreciative and loving, living under the fear or hope or threat of the knock on the door. A dread visit from the social worker, who might pass you along, around or back.

At the bottom, of course, the untouchable unlovables. The broken kids in care with the mark of Cain, the ones no one wants. My brother Christopher.

Residential care operated like dogs’ homes – abandoned pets kept penned until someone, anyone, might take them. I remember days my hair was specially brushed. I was told to smile, because new parents might see me, heal me, love me, take me off the city’s hands. There is a skill, you see, to being lovable: a fluffy, undamaged Disney dog, eager to engage, with a wagging tail. Christopher couldn’t or wouldn’t learn. People were nervous of his nervous tic. His face twitched, his mouth twisted. He was stunted. The runt of the litter with perhaps a subtle hint of trouble to come. Though appearances can be deceptive.

I was rehomed but would keen for Christopher until they returned me to the pack, just another ungrateful, undeserving boy. Until the days of Lilian and Dudley Drabble, their house on a Devon river, a kitten, a cat and a magic packet of nasturtium seed.

I grow it still, this unruly, gaudy flower. It is prone to infestation, the first to fall over in the frost, but my gardening is saturated in emotional memories, as with music and love. So I sow nasturtiums because they are tangled up like bindweed with thoughts of the boy I was, the boy I became, the brother I lost, perhaps the father I’ll never know. And I sow runner beans for Mary because Don, her late husband, grew them. Mary also offered me a home, a place to grow when I didn’t have one. So we talk about peas and radishes, about the rocket and lettuce I will sow when she starts treatment.

Later in the week, I meet with Howard to stir biodynamic cow manure by hand in water for an hour. From the beginning of working the allotment we chose to work this way, inspired by Jane Scotter of Fern Verrow farm in Herefordshire, the finest grower we know. In most areas of my life I carefully calculate risk and reward, working within tight budgets and remits. Here, it is different; organic plants grow, foxes are free, flowers spread, children run around. As an adolescent I was banned from confirmation class for being unable to buy into the church, the resurrection and miracles but I have since learned to suspend my disbelief. A journalist, I stop asking questions and try to listen. We follow a lunar planting calendar and avoid invasive pest control. We believe our crops last longer, taste better – the rocket is hotter, the beetroot sweeter, the sorrel more sour. It works for us. We feel more connected to the soil. It suits us and the space.

There is something deeply meditative about the stirring process, encouraging you to focus, to sit still for an hour at dusk or dawn, whatever the weather. Howard has to leave early, so I also spray the mix around Mary’s plot.

The next morning I am at the allotment early to sow rows for Mary and me. I am keen to catch up. I was exiled from the plot with a fractured ankle for four months over the winter. There was a disconnect from the soil with which my wellbeing is intricately entwined. Suddenly, catastrophically, walking and gardening, the twin chemical-free medications I have built into my life, were shattered along with my bones. I am rebuilding this connection now, but it is slow. I am back walking along the canal to work, over the heath or along beaches, but I have missed the overwinter planting that greens the brown soil that surrounds us. I have a thought the plot is sulking, like a cat or child that has been left alone too long. The three bean structures I have built on the two plots are prone to attack. The urge for organic slug pellets is strong.

Later, an allotment neighbour comes to talk over bad news. William, the kindly chairman of the association, has been found dead in his flat. I have always been grateful to him for the gentle way he defused tension between the plot holders and the helpers. William had been forced to leave his native South Africa when his student activism had come to the attention of the Afrikaans authorities. In London, he had written and directed successful plays, he had been a book reviewer, pictures showed he had been beautiful, but the William I knew was a shy, bespectacled man who grew tulips and peonies, and at whose plot I always stopped to talk about gardening, the weather and the problems with sharing sheds.

The slugs may be winning their battle with the climbing beans. The early salads have bolted. The garlic and shallots that had looked green and healthy only a few days ago have succumbed to papery rust and need to be pulled. The wild Tuscan calendula has spread like duckweed and is smothering other plants. For my first time in June, the plot is in need of a reboot. The living carpet that nor

mally covers the soil is threadbare and worn. A couple of weeks before midsummer I start again. It is hard sometimes not to think that your garden says something about you, the green fingers you hope you have, your innate ability (or inability) to nurture. Hard not to feel good about yourself when the plot thrives, or like a failure when it falls. The fault must be yours and not the seed, the weather or blight on the site.

Without early success at growing as a kid, I guess, I might not be doing it now. It was the first time as a child I thought I might be gifted at something. In south Devon, Dudley gave Christopher and me two pocket-sized patches of garden and two packets of seed. Christopher had African marigolds (tagetes): bright orange, cheery, the stuff of temple garlands. I was handed nasturtium flowers: chaotic cascades of reds, oranges and yellows (Dad liked bright colours), which soon overflowed. Caper-shaped seed heads would dry in the sun. I was amazed (still am) that so much life can come from a small packet. Later my nasturtiums would fall prey to black fly, a nightmare infestation sucking sugary life. Lilian showed me how to spray leaves and stems with soapy water, holding back the devastation until frost would turn their green into limp, ghostly grey; a silvery sheen of dew signalling the end. I would pull them, shake out seed for next year (though the self-seeding was always enough) and throw the lifeless bodies on the compost pile to rot down and turn into soil. This idea of nature’s renewal fascinated me. I was in love.

For the first few years at the allotment I helped with a primary school’s gardening club, where children from five to 11 learned to grow. Kids who might be having trouble settling in class worked together during Friday lunchtimes. Seedlings grown in the greenhouse were replanted in raised beds in the playground. I would host their visits to the site. Branch Hill, where we are, is like a Victorian secret garden: gated, only just domesticated, sheltered by tall trees. We would give the children sunflower seeds and watch them stand, stunned, as the plants grew faster than them. We would eat peas from the pod and taste herbs. One memory sticks: watching the blossoming of a Somali-born girl. At first head down and standing shyly at the back of the group, she began to join in, to enquire about sorrel, lovage and other flavours unfamiliar to her. By the end of the year, impatient at the gate, she would rush to ask for magic nasturtium, her favourite ‘spicy flower’.

-->

Plot 29

Plot 29